「丸太足場」についての インタビュー記事を 書きませんか?

今回そんなお声がけをいただいて、初めて「丸太足場」というものを意識した。京都に住んでもう15年になるので、街に出かけた際にどこかで見たことがある気はする。だけどそれをちゃんと意識したのも、伝統技術であることを知ったのも、その時が初めてだった。

取材現場は、知恩院塔頭の良正院。

門の中に入ると、今まさに足場を組んでいる真っ最中。細長い丸太が何本も本堂を取り囲み、まるで、外側にさらに大きな建物ができたかのように組まれている。

改めて見ると、大きく重厚ながらシンプルな作りで驚いた。格子状に組まれた重たそうな丸太は、鉄の線でぐるぐると巻かれているだけ。その上に板を置いて、職人さんたちが軽やかに行き来する。この構造は、もとをたどれば江戸時代以前には存在していたそうだ。

普段は注目されない、そしていつかは消えてしまう“仮設”としての「丸太足場」。

作っては解体し、作っては解体しながらも、その一時的な“仮設”を通して伝統技術が今に残っている。わたしにはその事実がおもしろく、ぜひお話をうかがいたいと思った。

「丸太足場」の技術を受け継いでいく職人さんたちは、いったいどんなことを考えながら仕事をしているのだろう。

普段なかなかお話できない職人さんたちを前に、少し緊張しながらインタビューに臨んだ。

丸太の足場が見られるのは 京都だけ

右から、今年で15年目の渕上さん(35)、職人歴40年以上・最年長の木下さん(62)、若手として活躍している最年少の西田さん(25)

土門:足場の素材には「鉄」と「丸太」の二種類があるとうかがいました。素朴な疑問なのですが、どうして今も重要文化財の足場は丸太で組むのでしょうか。そういう決まりがあるんですか?

渕上:京都府さんが、文化財修復技術継承のために丸太での足場づくりを推進しているんです。「文化財の修繕時には、技術継承のために丸太で足場を組みましょう」 って。以前はどこの県でも丸太の足場ってよくあったんですけど、その技術が今もちゃんと引き継がれているのは京都だけだと思いますね。

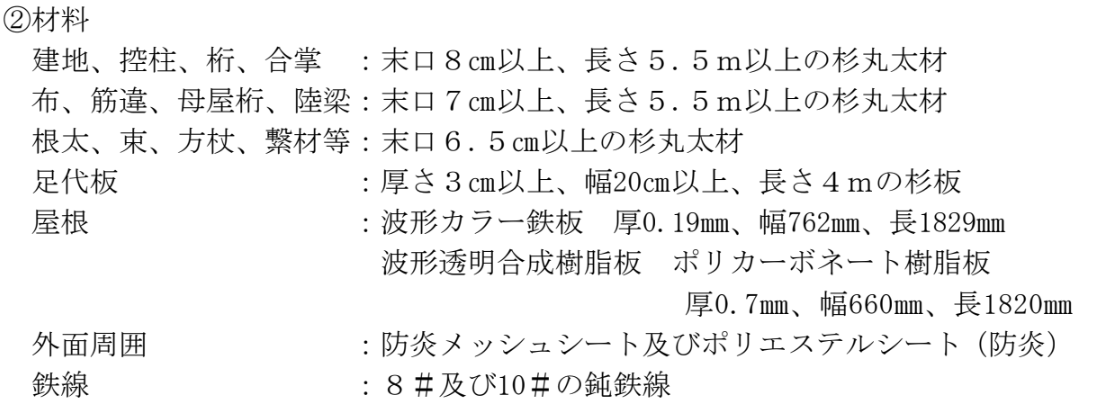

良正院の設計書の一部。丸太足場にも長さや太さの規格が明確に決められていることがわかる

土門:じゃあ、今丸太の足場が見られるのは京都だけなんですか。

渕上:多分今はもう、みんな鉄で組んでいると思いますよ。奈良なんかには残っているかもしれないけど。

土門:ちなみに丸太と鉄では、足場の組み方ってどういうふうにちがうんでしょうか。

渕上:そらもう、全然ちがいますよ。

木下:構造は一緒なんやけどね。いちばん大きな違いは、番線を使うか、クランプ(鉄製の締め具)を使うか。

土門:番線?

木下:番線っていうのは、鉄の線のことやね。これで丸太同士をぐるぐるっと巻いて縛るねん。クランプだったらインパクト(ドライバー)でバリバリ締めるだけやし早いんやけど。番線はすごい時間がかかるね。

渕上:昔からの道具で今も作っていますからね。丸太と番線と釘だけ。 あとは要所に穴開けてボルトを入れるくらいです。

土門:初めて近くで拝見しましたが、あんなに大きいのに、かなりシンプルな作りなんですね。番線の縛り方も無駄がなくて洗練されているというか。

渕上:そう、丸太の足場って、要は番線でくくっているだけ なんですよね。箇所によってくくり方は使い分けてますけど。

木下:番線をくくれる職人がなかなかいないんですよ。

とび経験者でも、鉄ばっかりやってきた人がこっちに来たら、

「これどうやってくくるん?」みたいな。いざくくってみても効かへんとかね。

渕上:今はどこも金槌でやってはりますからね。くくるのってうちだけちゃうかな。

土門:京都の中でも会社によってやり方が違うんですか。

渕上:やっぱり会社ごとのやり方がありますよ。他社さんがやってる足場見て「へえー、こんなふうにやってはんねや」って思うこと結構ありますしね。

この番線をくくれる職人がなかなかいないんですよ。 とび経験者でも、鉄ばっかりやってきた人がこっちに来たら、「これどうやってくくるん?」みたいな。いざくくってみても効かへんとかね。

木下

見て、やって、失敗して、 覚える

土門:そういう作り方って、どういうふうに継承されていっているんですか。マニュアルとか……。

渕上:ないですないです(笑)。もう教わるというよりは、見て覚えるって感じで。

土門:見て覚えられるものですか。

渕上:まあ要所要所は口で教えますけど、大部分は「見て、やって、失敗して、覚える」 みたいな。

土門:(西田さんを見て)そんな感じですか?

西田:はい、そんな感じです。

土門:へえー、すごい。

木下:僕らが若い時分は毎日のように怒鳴られてましたよ。上の人に「お前何してんねん」「そんなんちゃうやろ」って。

渕上:今はだいぶましです。昔はすごかったと思いますけどね。

木下:すごかったですよ、「帰れ!」とかしょっちゅう言われてたね(笑)。

土門:だいたい、何年くらいで一人前になれるものなんでしょう。

西田:僕なんかは今8年目ですけど、やっとちょっとわかってきたかなというくらいです。

土門:8年!

渕上:まあ、本人の意識にもよると思いますけど(笑)。僕は今15年目ですが、ここ最近やっと全体がわかるようになってきた感じです。

土門:15年かけてなんとか一人前って感じなんですね。

渕上:もうこちらの人(木下さん)はベテランですけどね。

木下:僕はもう43年になるね。19のときからやってるから。

木下さんが作った丸太足場の模型。交通事故で怪我に遭い療養していたときに、「やることがないから」とつまようじで作ったのだとか。

土門:ベテランから見て、丸太の足場でいちばん難しいところは何ですか?

木下:やっぱり、屋根がダレないようにするのがいちばん難しいね。木やから、どうしてもダレてくる。だから最初からまっすぐ作らないで、それを加味した上で組まなあかん。

渕上:歩道橋も、ちょっとアーチを描いているじゃないですか。丸太でもそれと同じことをやっているんです。30メートルくらい幅ができると、どうしても自重でダレてくるから。現場にもよるけど、たとえばここだとできあがってから5年は使いますから、5年後のことを考えながら作るって感じですよね。でもそれはもう、経験でしかわからないですよ。

木やから、どうしてもダレてくる。だから最初からまっすぐ作らないで、それを加味した上で組まなあかん。

木下

手間はかかるけど、 誇りを持てる仕事

土門:ところで、丸太で作った足場のメリットって何でしょう。鉄よりも優れているところというか。

木下:大工さんにとっては、丸太の足場の方が使いやすいみたいやね。重たい資材を吊るとき、鉄だと曲がってしまうことがあるけど、木だと粘りがあるって言わはる 。

土門:粘りがある。

渕上:鉄だと曲がってしまったらおしまいやけど、木だと反撥力があるんで戻ってくれるんですよ。しなりがあって融通が利く。せやし気兼ねなく重たいもんも吊れるらしいですね。

土門:作り手としてはどうですか。丸太と鉄だとどっちの方がやりやすいですか。

木下:うーん。丸太は難しいからね。

渕上:10:0くらいで、丸太の方が大変ですよ。 人も要るし時間もかかるし、倍ではきかないくらい手間がかかる 。 そこらへんで言うとデメリットしかない。 でも、技術継承のために京都府さんが取り組んでくれているので、こうして残していけてるんですよね。 大変だけど、やっぱりやってて楽しいのはこっちなんですよ。この仕事って、誰にでもできるわけじゃないですから。その誇りというか、プライドみたいなのはありますね 。

土門:誇りとプライド。

西田:僕はまわりに同じような仕事をしている人がいないので、「こういう仕事をしてる」って言ったら「すごいな」って珍しがられるんですけど、そのたびなかなか他ではできない経験をしている なって思います。

木下:僕も一緒やね。金閣寺さんや銀閣寺さんの仕事なんかしたら「すごいねえ」って言われるし。

土門:いつかは消えてしまうけれど、文化財のすごく近くにいる仕事ですよね。

渕上:その分、責任も重大なんやけど。

木下:物をつぶしたらいかんしね。足場って、修理が終わったら解体するでしょう。そのときが一番気を遣うわね。そこで物落としたりしたら終わりやから。 たとえばなんか落として瓦を割ってしまうとかね。平葺瓦ならまだましやけど、本葺瓦やったら、ほんま大変。一枚割ったら全部張り替えなあかん。

土門:それはこわい!

渕上:せやし、解体のほうが気遣います。 一番仕事で大事にしているんは「とにかく物を壊さないこと」 。これが大前提。直すために足場組んでんのに、壊してもうたら本末転倒やからね(笑)。それが守られてこその信頼だと思います。

土門:ちなみに解体する時には、寂しいという気持ちは湧いたりしないんでしょうか。

木下:そんなのあらへん(笑)。解体のときには潰さんようにって、それしか考えてない 。

土門:じゃあきれいに撤収できたら、やっと「仕事完了」みたいな。

渕上:はい。何事もなく終われたときの安心感はすごいですよ。最近、台風とか地震とか自然災害がすごいでしょ。やっぱりそれが怖いですよね。昨年の台風21号の時には、自分の現場の東寺さんまで見に行きましたもん。風すごい中、足場の一番上までのぼってね。そういう不安は常にありますよね。

木下:僕も台風来てる中「様子見てこい!」って言われて行ったことあるけど、暴風の中よう直さへん。風で飛ばされかけてたけど、見て見んふりして帰ったこともありましたね(笑)。

丸太足場は 「この人の仕事」だとわかるもの

土門:今回一番うかがいたかったのが、「仮設」であるということについてなんです。建物を作ったり修繕したりする大工さんは、手がけたものが後にも残りますよね。でも足場って一時的なもので、ずっと残るものではない。職人さんから見たとき、その魅力って何なのかなと思っていて……。

木下:……そうやねえ。確かに足場は、後に残らへんからね。

土門:そのおもしろさについて最後に聞いてみたかったんです。

渕上:言われてみて初めて考えたけど、何が楽しいんやろね(笑)。

土門:(笑)

渕上:うーん、でもやっぱり「素人にはわからないけど、玄人にはわかる凄さ 」じゃないですかね。わかる人には「これはすごい技術やな」ってわかる。それが楽しい。 あとはやっぱり、特別感を味わえるところ、かなあ? 「僕らは伝統を引き継いでるんだ」っていう、プライドとか誇りとか特別感 とか、そういうのは持っていますね。普通のとびだったら、自分はこの仕事続けられていないと思うので。

木下:僕も一緒やね。伝統を引き継いでいるっていう気持ちがある。

西田:僕も同じです。他では経験できないことがいっぱいあるので。

土門:伝統技術としての「足場」ってなんだか不思議ですよね。仮設だから一時的にしか見ることができないし、消えていく。そして新しく作るたびに、受け継がれたその技術自体、少しずつ変わっていっているんだろうなとも思うんです。

渕上:そうですね。先輩から教わった技術に、「次はこうしたらどうかな」って自分なりの工夫を付け加えていきますから。伝統技術でもあるし、渕上だけの技術でもあります。 だから、この現場はこの職人さんにやってほしいって、名指しで指名が来たりするんですよ。 「誰がやっても同じ」じゃない、「この人の仕事」ってわかるものなんですね 。 自分たちが受け継いできた仕事を、見てくれている人は見てくれている。それを感じる時は、やっぱりすごく嬉しいですね。

言葉でなく、 動きによって継承される伝統技術

初めは緊張感に満ちていた職人さんたちの顔が、語っていただいているうちに少しずつ柔らかくなっていくのが印象的だった。木下さんが作ったという模型を囲み、「ここから人が入って、ここにシートを張って雨風をよけて……」と楽しそうに説明してくださる。

「やっぱり、どんどんできあがってく時がいちばん楽しいですよね」と、渕上さんが言った。

最後に、丸太足場に実際に立たせていただいた。

足場に慣れていない私たちのために、職人さんがささっと階段を作ってくださる。ものの数分でできあがった階段を踏みしめ、私たちは中へと入っていく。頭上高く組まれた足場の上を、すいすいと職人さんたちが移動していくのを見ながら、ここにいるひとりひとりの体の中に「伝統技術」が染み込んでいるのだなと思う。

「作っているところを見られる機会は、なかなかないですよ」

それを聞きながら、私は彼の「見て、やって、失敗して、覚える」という言葉を思い出していた。

この瞬間に、伝統技術は継承されている。言葉ではなく、動きによって。

その瞬間が積み上がり完成した彼らの作品は、一時的に現れいつか消える。でも、修繕し終わった文化財には、守るように寄り添った気配として、彼らの伝統技術が残っているのだろう。

私が気づかなかっただけで、この京都の街には、そういう気配があらゆる場所に残っているのだろうな。

仕事場に戻っていく職人さんたちの背中を見ながら、そんなことを思った。

『POP UP SOCIETY』とは

『POP UP SOCIETY』は、一般の方に業界への興味を持ってもらい、中長期的に建設仮設業界の若手人材不足に貢献することを目指し、ASNOVAが2020年3月から2022年3月まで運営してきた不定期発行のマガジンです。

仮設(カセツ)という切り口で、国内外のユニークで実験的な取組みを、人物・企業へのインタビュー、体験レポートなどを通じて紹介します。